As the weather starts to heat up, no dessert screams "summer" as much as ice cream!

It's one of those classic treats that everyone takes for granted, but when it comes to the full range of flavors and that good old nostalgia factor, ice cream just can't be beaten.

While plenty of people today love their frozen treats, you may be surprised to know that ice cream's history goes back longer than you'd think. In this post, we'll trace the sweet treat's origins and look at how ice cream evolved to the kind of desserts today.

Perhaps the first ice cream cup in existence dates back to 2700 BCE. Supposedly, in the tomb of a Second Dynasty Egyptian king, archaeologists found a cup or mold that many sources claim was meant to hold an early version of ice cream—snow or crushed ice in one rounded half, and cooked fruit in the other.

Some believe that this is the earliest evidence that humans have always enjoyed their frozen treats. However – there's not much archaeological evidence to either confirm or deny the purpose of this strange, buried Egyptian cup and mold.

The Egyptians, it should be noted, did have the ability to 'make' ice – or at least, use a natural process to get ice. Shallow pools of water exposed to the night sky in the desert can freeze above 32 degrees Fahrenheit – a process called radiative cooling. It sounds wild – but even though they probably didn't have ice cream as we know it, Egyptians certainly had ice.

For those who doubt the Egyptian cup's role as an early form of the ice cream cone, the history of ice cream – or at least icy treats – really begins in the Achaemenid Empire of Persia (modern-day Iran).

Continuing the ice in the desert discussion, in as early as 500 BCE, the Persians were known to enjoy ice or snow mixed with honey and natural flavors. The Persians were likely the first to build natural evaporative cooling ice houses – known as yakhchāl – which allowed cool air to flow into a cone-shaped building and keep the interior at a low temperature.

Some of the most popular ice flavors in ancient Persia were rose water, saffron, or fruit syrups. Especially during the hot, dry summers, this early precursor to ice cream was considered a great delicacy.

Today, we'd probably consider their version closer to shaved ice, but it was still the first step towards the ice cream we know and love today!

A few centuries later, in China, another major step was taken to bring ice cream closer to the form we all know and love here in the 21st Century. The Chinese version of ice cream was the first to use milk, which added a creamy texture and flavor to the shaved ice treat enjoyed by so many other nations.

In addition to using milk, the Han Dynasty Chinese were the first to use a salt mixture to lower the ice's temperature. This allowed them to make ice cream faster, and a similar method is used in at-home ice cream makers today.

Growing up as the son of King Phillip II of Macedon, the young Alexander the Great was known to enjoy eating frozen milk. As he grew older and expanded his kingdom into the empire that we know as Ancient Greece, he spread his love of this early kind of sherbet across the lands.

Hippocrates is often considered the father of modern medicine. He encouraged his students to eat "ices" in the morning to "liven" the blood and increase general well-being. (He was almost certainly talking about something closer to a shaved ice with fruit syrup rather than ice cream.)

During the rule of the Roman Empire, "ice cream" and frozen ices were popular treats. One famous ice cream fan was less famous than Alexander the Great... but perhaps a bit more infamous. Emperor Nero was known to enjoy ice mixed with various fruits.

Because the emperor often traveled throughout the kingdom, Nero's personal attendants had to cart ice down from the mountains to ensure that their monarch would soothe his sweet tooth whenever he felt the urge. Ices and ice creams were extremely popular among the rest of the Roman nobility and the common folk.

During the Tang Dynasty of China (618 to 907 CE), the iced milk that had been so popular in earlier dynasties had become a widespread delicacy. While it was still more common among the upper classes and the nobility, it was quickly becoming more accessible to people of all ranks.

At roughly the same time in Italy, ice cream was still a long way away, but sorbets were becoming a fairly common frozen treat. Marco Polo's famous travels to the Far East in the late 1200s may have been the first time that something resembling modern ice cream made an appearance in Europe, but regardless of its exact origins, ice cream really took off in Italy first.

Regardless of whether Marco Polo introduced ice cream to Italy, it really gained in popularity starting in the 1500s. A few Italians might even lay claim to the title of Inventor of Ice Cream – at least the modern type as we'd recognize today.

At a contest of unusual foods organized for the Medici court, a man named Ruggeri – a chicken farmer(!) – won with his "frozen dessert" which was something like ice cream. When the Italian Catherine de' Medici married the French King Henry II years later in 1533, she brought her fondness for sorbets and frozen ices – and supposedly, she temporarily convinced Ruggeri to tag along as well.

Alas, a personality clash in the kitchen sent Ruggeri packing back to Italy – but as he left, he supposedly also shared the secret to his desert with Catherine. The sweet treat quickly became a hit in France, and eventually, most of Europe never looked back.

Around the same time another Florentine in the Medici court, Bernardo Buontalenti, was renowned for his mixture of cream, lemon, orange, and bergamot—a flavor combination that wouldn't sound out of place in many modern ice cream parlors! Finally, in England in the 1600s, King Charles I paid his ice cream maker a lifetime pension to ensure that the recipe would remain secret and thus enjoyed only by royalty.

Outside of the nobility, the 1600s also saw the beginning of ice cream's spread among ordinary citizens.

Chefs such as Procopio Cutò – a Sicilian – continued to develop their ice cream recipes to the point they could store and sell them to the mass market. Cutò eventually opened the Café Procope in Paris, which was renowned for its frozen delicacies.

The Café closed for a roughly 50-year span starting in 1872, although it did reenter business as a cafe in the 1920s. If you allow the brief respite, you can still eat ice cream at the Café Procope today!

Long before European colonists landed in the Americas, helados de paila was a popular treat among the Caranquis or Cara. Ice was brought down from the mountains of modern-day Ecuador, packed with straw to keep cool during the long journey.

After filling a large cauldron with ice or snow, the Cara would add fruit juice and milk. This mixture would be vigorously beaten until the ice was thoroughly mixed with the ice to create a refreshing sorbet. In some parts of Ecuador, this traditional method of making a frozen dessert is still practiced today!

Quaker colonists were among the first to introduce ice cream to colonial America. The first ice cream ad ran in the New York Gazette in late 1773, and after that, it was a common sight at confectioner's shops in many major cities.

George Washington was known to love ice cream. In the summer of 1790, he spent more than two hundred dollars on ice cream alone—more than five thousand dollars in today's currency!

Thomas Jefferson had an early recipe for ice cream and helped popularize the sweet treat by serving it to his guests at Monticello.

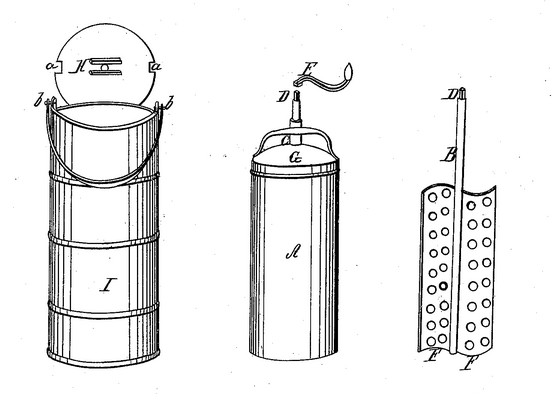

In 1843, a woman named Nancy Johnson created the first ice cream machine. It may have been little more than a hand crank that turned a series of nesting barrels, but it was revolutionary for the ice cream industry.

By 1851, mass production of ice cream had taken off, and dairy kingpins like Jacob Fussell quickly found that the frozen confection provided a convenient product from the extra cream and fat that their dairy businesses often had left over.

With the new usage of the industrial fridge (1870) and the invention of the safer refrigeration process using freon (the end of 1928), ice cream solidified its spot at the international table.

Ice cream hit the grocery store shelves in the 1930s and quickly established their place at the center of the American cultural consciousness. During World War II, the largest producer of ice cream was actually the US Army!

Ice cream was served to troops to boost morale and instill feelings of patriotism and home spirit.

The link between the US and ice cream was so strong that in Fascist Italy, Dictator Benito Mussolini banned ice cream (!). Once the war was over, however, ice cream rocketed back into popularity around the world!

The first appearance of the ice cream cone is a little bit harder to pin down. Since at least the 1760s, people have been rolling wafers into a 'cone' like treat.

A French cookbook from 1825 describes the use of "little waffles" that could be rolled into a cone shape and used to serve ice cream. An English cookbook from 1888 describes the actual process of making "cornets" that were baked with almonds in the wafer and filled with cream.

However, most people agree that the moment ice cream cones went mainstream came at the St. Louis World's Fair in 1904. A Syrian and Lebanese concessionaire named Arnold Fornachou ran an ice cream booth and realized that he was running dangerously low on paper cups. In desperation, he struck a deal with the owner of the waffle stand next to his own booth.

The waffles that the adjacent stand had rejected for being too thin were rolled into a cone shape, pressed with a heating iron, and the waffle cone as we know it today was born!

While some – I won't weigh in here – have suggested that this story is more of an urban legend than an actual historical fact, it nevertheless remains one of the more famous ice cream stories that still lingers in the American consciousness.

Like the ice cream cone, the ice cream sundae has a wide range of conflicting backstories. What most people do agree on is the fact that the ice cream soda came first.

In 1874, Robert McCay Green ran a soda fountain in Philadelphia. After a newer, fancier soda fountain opened up just down the street, Green was searching for a way to keep customers coming back for more.

His big idea—vanilla ice cream in plain soda water—was an overnight success. Soon, Green expanded the idea by offering up to sixteen different syrups to flavor the soda water, and the ice cream float was born! According to the common legend, however, in the religiously conservative (at the time) state of Philadelphia, this drink was seen as dangerously hedonistic – and unsuitable for Sundays, the Sabbath day.

Philadelphia's strict "Blue Laws"—laws that dictated what you could or couldn't do on Sundays—decreed that no soda was to be served on what was considered "the Lord's Day."

As a result, soda shops began selling ice cream sodas without the soda. This mixture of syrup and ice cream underwent a quick name change to avoid angering the religious government, and the world finally had its first Sundae.

While this is the most famous story of the ice cream sundae's birth, there's not too much in the form of hard evidence to support it. Instead, Platt & Colt's Soda Fountain in Ithaca, New York, has a compelling claim. They have printed proof of their first ice cream sundae made with cherry syrup and vanilla ice cream.

You be the judge!

Soft serve ice cream is made in mostly the same way as traditional ice cream, with one major exception. In soft serve ice cream, air is injected into the mix during the freezing process. This creates a lighter, softer feel and provides soft serve ice cream with its characteristic fluffiness and flavor.

There are two main claims to the invention of soft serve. The ice cream company Carvel claims that their founder, Tom Carvel, had his ice cream truck break down one day in 1934 as he was doing the rounds. As it was a warmer day, the ice cream in his inventory began to melt, yet he sold out in record time! Carvel concluded that softer ice cream sold better and began working to manufacture soft serve ice cream in the future.

The other major claim comes from Carvel's competitors at Dairy Queen. According to the soft-serve chain, J. F. McCullough and his son invented the soft serve formula in 1938 and sold out within two hours of debuting their product.

Another interesting – though dubious – claim comes from across the Atlantic.

Future UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher is often erroneously cited as having invented soft-serve ice cream in the 1940s. However, even though Thatcher's work as a chemist for a major food producer is well-documented, this is just a myth.

Nearly every country today has its unique variation on the internationally beloved ice cream. While the basic idea is the same, each version's differences reflect the local tastes and preferences.

In Italy, gelato has a lower fat content and much less air, which creates a smooth, dense texture with a creamy taste. Similarly, in India, kulfi is made by reducing the amount of milk to create a creamy ice cream variation so thick that it can be served like a popsicle!

Mochi is quickly growing in popularity around the world, but it got its start in Japan as a small ball of ice cream wrapped in a sheet of rice flour dough. In Thailand, i tim pad is a thinly rolled type of ice cream that got its start as a popular street vendor treat, but is increasingly common in the US as well.

In Turkey, dondurma is a variation on ice cream that includes whipped cream and ground orchid tubers. Pagoto, in Greece, is sort of a mixture between gelato and dondurma, which makes a lot of sense given where Greece falls between Italy and Turkey.

Finally, in Germany, vanilla ice cream is extruded through a pasta maker, topped with strawberry sauce, and garnished with chopped nuts or white chocolate to look like a plate of spaghetti with Parmesan cheese on top!

No matter where you hail from, ice cream and its many variations are some of the most beloved treats worldwide!

Today, there's no question that ice cream is the most internationally beloved treat in the world.

In the United States alone, 1.53 billion gallons of ice cream are produced every year. The average American eats around 22 pounds of ice cream a year, and that number doesn't seem to be getting smaller any time soon.

According to a recent poll, the most popular ice cream flavor is chocolate. Vanilla comes in second place, followed closely by classic flavors like cookies n' cream, mint chocolate chip, rocky road, and cake batter. The most popular topping is hot fudge, with nuts, chocolate syrup, Oreo cookie crumbles, and sprinkles listed after.

Perhaps the biggest challenge to the icy throne is frozen yogurt. Between 2008 and 2009, the number of frozen yogurt shops in the United States more than doubled, while ice cream consumption nationwide dipped ever so slightly.

Wisconsin is the largest consumer of ice cream in the US, but the residents of Long Beach, California place first in their love of the frozen treat.

So there you have it – ice cream has had a zany and interesting path to becoming the king of desserts. From its possible travels on the Silk Road to the apocryphal stories it has inspired around its variants and spinoffs, you know it won't decline in popularity any time soon.

So—consider the long history of the treat the next time you order two scoops in a waffle cone. Whatever the true history, you're just glad it exists when you take those first bites. And if you enjoy ice cream (and its history), check out my post on the history of eggnog, its liquid cousin.