If you ask me one thing that my daughters would drop anything to eat – it's fresh bread. Sourdough, white bread, whole grain bread – it almost doesn't matter the type in their eyes.

But isn't bread fascinating? Like you, I wondered about the history of bread – so I set out to trace this staple food from its early emergence to its current form.

So let's slice through the mysteries – let's discuss bread.

Archaeological evidence suggests that hunter-gatherer societies around 22,000 years ago already had the means to turn grains into flour and bake rudimentary types of bread. Findings from Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, and the Fertile Crescent show that bread was an essential part of everyday life thousands of ago.

However, bread production has come a long way since then.

Farmers began growing and cultivating crops about 12 thousand years ago. But despite the number, the history of breadmaking goes to at least 10 thousand years before humans even thought about growing wheat and barley in their farms.

In one archaeological excavation, the scientists studying in Ohalo II—an old hunter-gatherer settlement in Israel—opened a new window into the history of bread.

In this 22,000-year-old site, the researchers found remnants of barley starch and a circle of chipped embers – signs of an open alternative to ovens and a tool for baking bread. This significant evidence indicates that making bread was already a well-established activity before humans became largely agricultural.

Another example that signifies the early emergence of bread relates to the archaeobotanical investigations in Shubayqa 1—an ancient foraging site in North-Eastern Jordan, dating back to the time of Natufian culture—9,500 to 12,000 BCE.

Archaeologists discovered two big fireplaces in an old structure – one of which contained different kinds of flours. They cataloged 24 bread-like types of remains. They found mainly crucifers, legumes, barley, oat, and einkorn wheat.

By examining flour-like particles and grinding stone tools in the ancient village, scientists learned that those residents were adept at sieving grains, making flour – and turning it into high-quality bread. Therefore, just as in Ohalo II, breadmaking was probably a routine activity for the Natufian people.

Scientists measured the height, width, and length of the pieces of bread they found in Shubayqa 1 to visualize bread in ancient times.

You've probably heard this story: early forms of bread were surprisingly similar to the unleavened flatbreads that were also cooked in old Mesopotamia, ancient Egypt, and by the Indus civilization.

Flatbreads are relatively thin, featuring at least 1-millimeter thickness. However, depending on the baking method and ingredients, they can be as thick as a few centimeters – but all-in-all, they are nothing compared to the loaves of bread on the shelves today.

Flatbreads were also popular among the Fertile Crescent populace—a crescent-shaped region in the Middle East that spans from modern-day Egypt to the western fringes of Turkey and Iran.

As the first farmlands of the world, whose residents began cultivating wheat and barley around 8500 BC, the hunter-gatherers of the Fertile Crescent were most likely among the first to make bread in a permanent place.

As you saw, 22,000 years ago, our ancestors were making ancient flatbread over open flames. But it's not like breadmakers and advanced ovens came overnight – cooking and baking methods also evolved.

One basic baking method in bread's history was to bury the bread under a layer of sand, embers, and ash – "ash-baked bread." (Similar to taguella.)

Of course, woodfire and vertical ovens were also popular – and closer to how bread is made today. Vertical ovens are cylindrical and typically made of clay, and may be portable or fixed in location.

The vertical clay oven originated in the Syrian–Mesopotamian area, and there's evidence that people throughout the Middle East and North Africa used these ovens extensively. Archeologists have found remains of these ovens from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, and Egypt.

In Arabic, the vertical oven is often called a "tanur" or "tanour." It originated from the Akkadian word "tinuru." Multiple variants of the word exist in different languages from Turkish (tandir) to Persian (tanur), Georgian (tone), and even Hindi (tandur).

Bread was a staple food for Egyptians – for everyone from the pharaoh to the peasants. Egyptians even used special types of thick, non-porous bread as containers for other dishes. This bread was easier to bake than leavened flatbreads since it didn't need a vertical oven.

Around 450 BC, Egyptians figured out that they could make these portable meals using whatever grain was most abundant. This discovery later led to an uptake in agricultural activities, larger villages and settlements – and consequently, the creation of cities worldwide.

And the Egyptians were more advanced than you'd think. In the Dynastic Period, Egyptians could remove wheat chaff without turning roasting or other special mechanisms. But large-scale production was hard, and only the rich had access to free-thrashed bread wheat. Others had to use emmer wheat.

Egyptians probably played a large role in the widespread use and advancement of bread. They had excellent trade relationships with the Greeks and exported bread wheat – and their bread baking knowledge – to Europe. Also, historians know yeast-fermented breadmaking was mastered in Egypt – early leavened bread. So Egypt possibly gave us some early examples of sourdough – and beer (although it's true: the Sumerians first created some inferior brews!).

The first bread-baking efforts in history go back to when our ancestors started harvesting grass grains. They'd smash the grains and mix the resulting powder with water to produce a soupy, gelatinous-like ingredient. They then shaped that paste and turned it into loaves of bread. But that wasn't the last bread innovation, as you well know!

In the times of the Old Testament, baking bread and its associated tasks were either a slave's job or a job for women. In about 300-150 BCE, however, the history of bread took a large turn when the baking industry started to thrive in the Roman Empire, and free men began considering bread-baking a decent occupation.

Soon enough, there were hundreds of master bakers around Rome. The popularity of baking jobs led to high regulatory scrutiny and the initiation of the Baker's Guild in 168 BC. The Guild's rules were rigorous – once apprenticed, bakers, their kids, and grandkids couldn't withdraw from the practice. They were also forbidden from joining the theater (a lower-class activity at the time).

By all accounts, the Romans made excellent bread. During this period, the Romans brought their beer brewing expertise into the bakery field and started to add yeast to their doughs to produce a sourdough and bake a wonderful, fluffy leavened bread.

Rome also gives us two fascinating developments in the history of bread. First, with the Edict of Diocletian, or Diocletian's Edict on Maximum Prices of 301 CE, we see early evidence of maximum prices on grains – in this case, spelt. And bread was certainly political – before that, the poet Juvenal coined the phrase Bread and Circuses. Bread and Circuses, or food and games, was his cynical take on all politicians needed to supply to appease the Roman population.

The Romans and the Greeks preferred white bread over dark because, at that time, color was an important factor in distinguishing bread quality. White bread requires sieving the bran and germ – much harder than other forms of processing.

Therefore, the educated and affluent class tended to eat different white bread types. On the other hand, those of lower status couldn't afford to buy white bread and settled for the darker loaves.

In Greece, many people were poor peasants who had to farm grains to pay their taxes and earn some money to eke out a meager living. As a result, they never had enough money to buy an oven and had to sell their grains to a baker, only to get some dark bread in return.

At the time, most bakers didn't own bakeries. Instead, they used to bake bread in their homes or even the public ovens and bring them into the streets to sell.

The Greeks prayed to the goddess Demeter—the goddess of harvest and agriculture—to increase their productivity so that they can have more grains and, therefore, more flour to bake bread.

Also attributed to the Greeks: in the 5th century BCE, we see the first emergence of the Olynthus Mill—also known as the hopper rubber—to turn grains into flour. The mill was composed of rectangular-shaped lower and upper stones. This hand-driven mill drove the massive production of flour in Ancient Greece, which meant more access to flour and bread.

The Romans and Greeks aren't the only cultures with a rich history of bread.

Gaius Plinius Secundus, famously called Pliny the Elder, was a Roman author and naval commander who traveled to various regions.

In his writings, Pliny talks about the exquisite taste of the bread made in Gaul—a region in Western Europe on the Iberian Peninsula. Residents of these areas used the foam from beer fermentation in their baking process, which gave their bread a unique lightness and taste.

Persians also had great accomplishments in the baking industry. While the Greeks and Romans were experimenting with water, they were among the first people to invent windmills, in around 600 BC.

The linked windmills – the so-called Nashtifan Windmills – are 65-foot-tall windmills that still stand in a small village near the Iran-Afghanistan border. Those particular mills have worked for an estimated 1,000 years.

Vikings had a relatively healthy diet, which included lots of bread. They were skilled at making a popular form of rye bread that still exists today. In addition to rye flour, its ingredients include dried yeast and honey.

Despite its significance in people's diets, not everyone in Europe had equal access to bread. Although medieval physicians used to recommend people eat refined, healthy, white bread, poorer people had no other choice except buying darker bread made of oats or rye.

In fact, the most dominant type of bread in rich people's diets was the trencher.

Trenchers were thick flatbreads that served as a plate for wealthy people, and held their other dinner foods, such as meat, sauce, and mashed potatoes. After finishing the top foodstuffs, people could finally eat the trencher, or give it as a donation to the poor.

After the further rise of commercial banking and the collapse of the traditional home bakery, new milestones in the history of bread came about through two types of regulation:

Guilds were joint organizations that obliged their members to obey specific regulations, and, in return, would offer some protection in the form of trade restrictions.

For example, members of a guild could ensure access to cost-efficient raw materials, safety, and financial assistance whenever their business incurred a loss. In other words, the guilds served as insurance coverage for the bakers' society. Around the 8th Century CE, we saw the first emergence of Baker's Guilds in Western and Northern Europe.

While the guilds were the baker's guarantee of safety and support, assize laws assured low-priced and good-quality products for customers. Like the Edict of Diocletian in 301 AD, the famous 13th Century England Assize of Bread and Ale put maximum prices on wheat products.

This law – and others like it – worked against guild monopolies to prevent bakers from misusing their power – and consequently, overcharging the poor. Based on the assize laws, a baker who breached these regulations or sold expensive bread was condemned to predetermined fines or even whipping.

Curiously, through this mistrust and the emergence of the regulations, the concept of a baker's dozen – 13 or 14 pieces – emerged.

The word 'doze' is synonymous with the number 'twelve.' But, to avoid government fines and punishment, bakers would give their customers an extra loaf for every 12 loaves they bought. Some even went so far as to giving two extra rolls for every 12. This is why the baker's dozen usually equals 13 or 14.

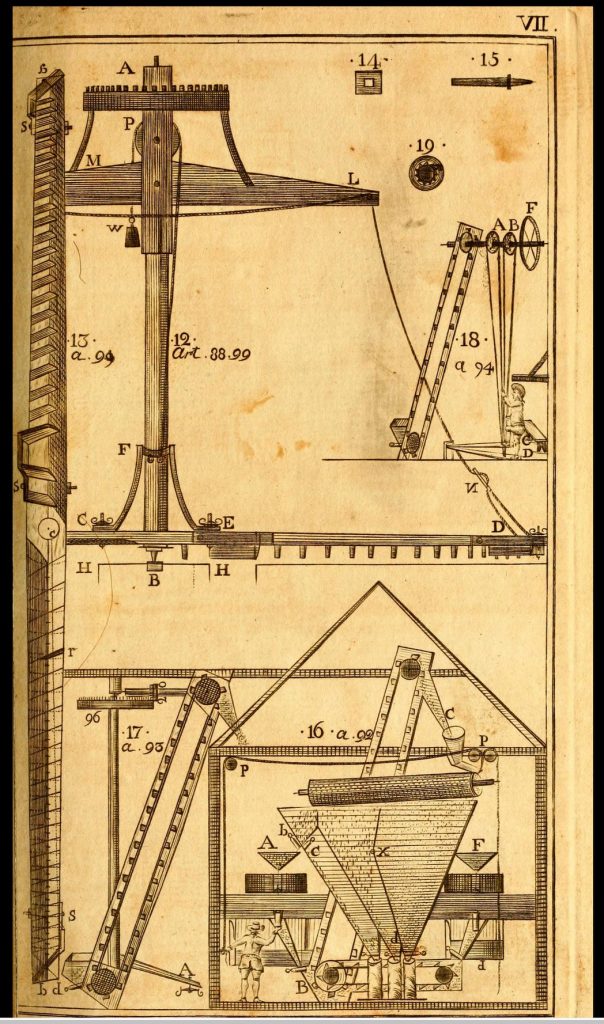

With the growth of breadmaking in the medieval era, the number of gristmills – cereal grain grinders – increased rapidly in the 10th century. From the 1086 AD Domesday Book from William the Conqueror, we know there were 5,624 water-powered gristmills in England, around 1 for every 300 citizens at the time.

Gristmills popped up all over Europe. You can see particularly well-preserved mills even today in Europe and throughout Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran.

After the first industrial revolution, in 1782, an American inventor named Oliver Evans was the first to design a fully automated flour mill. Evans was a well-known businessman and engineer of his time, who designed and built the first automated industrial process – he built all manner of steam-powered vehicles and machinery after his success with the mill.

Before Evans' innovation, every single step of the milling process was labor-based and very time-consuming. Inspired by marine applications, Evans even designed a bucket elevator for his flour mill to help pass the crops and flours through different parts of the mill.

After that, he further improved his machine and automated the cooling, drying, sieving, and packing steps. This smart automation procedure saved tons of hours spent by laborers and accelerated the whole breadmaking procedure. You can thank Oliver for laying the tracks to supermarket bread today.

In 1834, a Swiss engineer—Jacob Sulzberger—invented the steel roller mill. Instead of crushing the grains as with stone grinding, these new mills could separate germ and bran by applying slight pressure on the grain. This new method produced extremely high-quality white flour for the baking industry.

At the same time, Alfred Bird, a chemist and food manufacturer in England, developed the first version of baking powder. Baking powder was the first real alternative to yeast, which helped to leaven dough and lighten the texture of bread with acid reactions.

We owe our present cakes and cookies to Bird's wife. Mrs. Bird had a yeast allergy, which motivated Bird to look for an alternative. We probably would've seen a significantly different timeline for cakes and other pastry products if it wasn't for her food intolerance!

About three decades after Bird's efforts, an American named Eben Norton Horsford created the first double-acting baking powder. Unlike Bird's single-acting baking powder, it didn't make carbon dioxide bubbles before heating.

These new attempts at baking powders gave a better taste to pastry products than the fragmented ones and would increase the flavor and speed of the bread-baking procedure.

In the early 1900s, Jackel and Diachuk discovered that if they add tiny amounts of an oxidizing agent—such as ascorbic acid and cysteine—into flour, they can enhance the physical characteristics of the resulting dough and produce more desirable baking products. Oxidizing agents act as if they 'age' the dough, making it easier to handle and quicker to rise during baking.

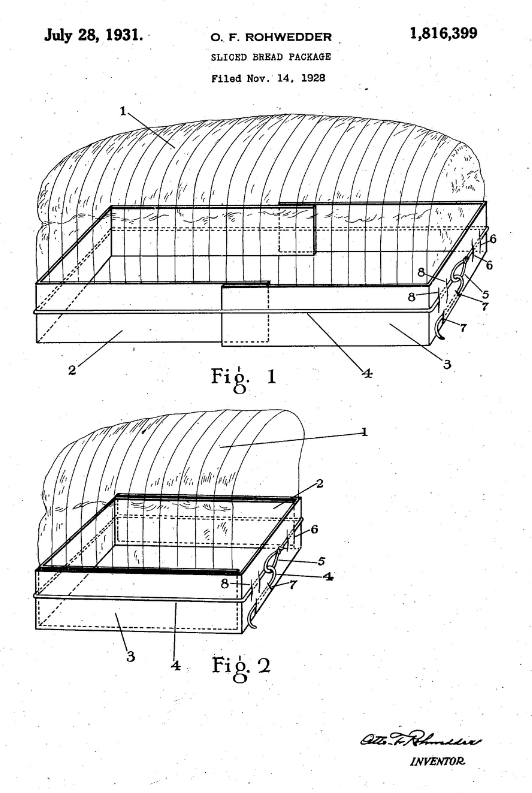

Even wonder who invented sliced bread? In 1927, Otto Frederick Rohwedder, another American inventor, developed and commercialized the first automatic bread slicer.

His ingenious device not only sliced bread but also wrapped the slices up in packaging.

Baking powders and the slicing machine were great contributors to the success of the baking industry. However, the progress didn't end here – but they certainly left us plenty of jokes about the best invention since sliced bread.

Soon after the invention of the automatic bread slicer, there was a major milestone in the history of bread when a popular American brand emerged. Wonder Bread was founded in 1921 but rose to prominence only when it started selling pre-sliced bread in 1930.

That joking expression – "that's the best thing since sliced bread" – was more Wonder Bread-inspired than Rohwedder-inspired.

With Wonder Bread's innovation, bread slices were now more uniform and even easier to eat. People started eating more bread because it was easier to prepare than almost anything else – you just had to reach and get another slice.

In 1943, during World War II, the head of the FDA Claude R. Wickard ordered a ban on pre-sliced bread due to inappropriate packaging (maybe – Wickard apparently thought the bread packaging was wasted on bread). But the ban didn't last more than two months – Americans heavily objected to the decision.

Another important bread-related event during the Second World War was bread fortification. At the time, American soldiers suffered from poor nutritional status. The US had already gone down the fortification road – adding iodine to salt in the 1920s.

The next solution? In 1940, the Committee on Food and Nutrition (now Food and Nutrition Board or FNB) recommended the addition of thiamin, niacin, riboflavin, and iron to flour. The FDA and the American Bakers Association got together and started enriching the nation's flour in 1942. Within a year, the authorities enacted the first War Food Order.

After the war, in 1946, the order was repealed – only to be replaced with new regulations in 1952. Nowadays, bread fortification isn't mandatory anymore, but "enriched" products have to meet specific standards.

During the 70s and 80s, nearly all bread was mass-produced using large and complex machinery. However, shifting health consciousness coincided with people craving hand-made bread made from ancient processes – and now called artisan bread.

It's ironic how things have come full circle—from thousands of years ago when people baked bread by hand to now where small-batch is again a form of art.

Today, Ukraine, Bulgaria, and Turkey have the largest per capita consumption of bread.

In the US, bread is extremely popular – over 95 percent of Americans say they consume bread regularly. Moreover, in 2019, almost 200 million people chose whole wheat or multigrain bread, and 10.21 million households ate five loaves/packages of bread in a week.

We aren't starved for varieties of bread today – far from it. But before we got to supermarket bread aisles, bread traced a fascinating path amongst our ancestors.

From unleavened flatbread to yeast-driven leavened bread to the pre-sliced bread on the shelves today, bread is here to stay. So the next time you eat some bread – or my daughters steal a slice – let's keep the bread innovations in mind!

Gerard,

this is a very deep dive into the history of bread. I enjoy reading your well researched posts. For those of us focused on cooking and eating great food at home, there is a lot of ideas and information. Thanks.

I was born in 1956 in North Carolina.

Was there a whole wheat option then or was enriched white bread considered the healthiest?