If you ask me, "what makes for a quality kitchen knife?" – ignoring the specific type – my thoughts often drift towards Damascus Steel blades.

These blades – through reputation and (well, sure) marketing – have a well-deserved reputation as durable, sharp, and attractive blades... and as all-stars in your kitchen.

Today, let's dive headfirst into Damascus steel. We'll discuss the origin of their allure, the history of "real" Damascus Steel, modern reproduction attempts, and some of the aspects that make those original blades so desirable.

Damascus steel likely has its roots firmly planted in Syria. "Damascus" is the capital city of Syria, renowned for its sword-making prowess – and is the leading contender for the origin of the word.

It's not the only contender, however. 'ḍamma' – ضَمَّ – in Arabic means to join or gather, while 'ma' – ما – is water – is it possible something about the joined layers looking like water explains it? Well, I don't know – but it's certainly possible.

Exactly how "Damascus Steel" was coined is lost to history. We don't know whether the name soldiers on today because swords were made in Damascus, although there was a large weapon-making tradition in the area. Syria – or somewhere in the Near East – imported patterned, high-carbon Wootz steel from India or Sri Lanka, and after that, the weapons industry took advantage of the high-quality ingredients to craft legendary blades with multiple layers of steel.

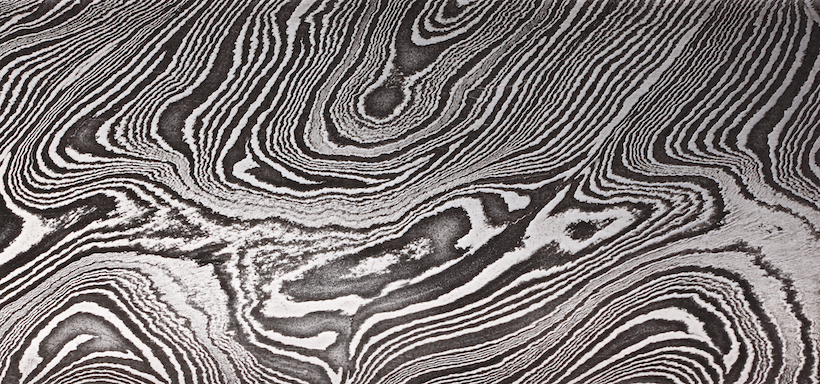

In modern times, Damascus Steel generally refers to the distinctive banding patterns which result from multiple welded layers of stainless steel. While we've lost the original methodology for forging these blades, modern processes produce a distinct (and unique) pattern, which is as beautiful and durable as the originals.

Blades made from the infamous wootz steel create the intricate and artsy blade styles you recognize in historic Damascus blades. Although they may look similar, a blade's origin and forging process might sway a bit from Damascus.

Let's talk a bit about Wootz steel.

Originating in South India, many literary texts address the history of the world-famous high-carbon wootz steel. The word "wootz" is probably a corruption of "ukku," which is the word for "steel" in several different languages in South India.

It wasn't until around the end of the 18th century that the word migrated to English, and Europeans delved into the makings of the steel.

As of publishing this article, we don't have a record of when wootz steel came to be. We do have evidence that wootz steel was circulating around the 4th century BC during Alexander the Great's campaign. Even earlier, a recent study uncovered a high-carbon (.9-1.3% carbon content) sword near Tamil Nadu, India dating back to the Iron Age – possible as early as the 6th century BCE.

All of this is to suggest: humanity has been working with high-carbon steel for longer than we might imagine.

The diversity of patterns characterizes wootz steel; both the look and color are different in each steel band. However, in modern times, what we now refer to as "Damascus Steel" does not refer to the wootz steel metallurgists in the 18th & 19th century recognized.

The original process included smelting iron ore to yield wrought iron, then heating and hammering it to beat out the slag. Another method was to heat magnetite ore in a sealed crucible while in the presence of carbon – creating the noted high-carbon blend.

Although wootz blades have tell-tale patterns, not all of them necessarily have recognizable patterns. When there was a pattern, it probably differed because of the smith making the steel (and his training). The patterns could be influenced by a combination of hammering, etching, and even dyeing.

Perhaps this type of steel gained its legendary status from the ancient techniques and material from which it stems – and the tales of its toughness and beauty. Without the process – or the special something in Indian Wootz steel – Damascus steel never would have come to be.

Let's clear something else up before delving in: "Damascus steel" is another umbrella term referring to different things. Or, maybe worse – a marketing term calling to mind the ancient blades.

J.D. Verhoeven, A.H. Pendray, and W.E. Dauksch published their explanations of what was different about the old process. They concluded:

"Based on our studies, it is clear that to produce the damascene patterns of a museum-quality wootz Damascus blade the smith would have to fulfill at least three requirements. First, the wootz ingot would have to have come from an ore deposit that provided significant levels of certain trace elements, notably, Cr, Mo, Nb, Mn, or V."

Also, they nodded to the fact that steelmakers probably passed down their methods orally – and secretly:

"The smiths that produced the high-quality blades would most likely have kept the process for making these blades a closely guarded secret to be passed on only to their apprentices."

Of note, Alfred Pendray and John Verhoeven did publish a paper on their modern attempt to reproduce the old process. Pretty neat!

Most of the modern "Damascus" steel blades might be more appropriately labeled "Damascus-style" blades. Well, save a few attempts at reproducing the ancient process (we'll hit those next).

The most common method that goes into Damascus Steel nowadays is to pattern weld metals of differing composition into a billet, or a casting meant for processing to the finished knife.

Just because the Damascus steel forging treatment was lost centuries ago, that isn't going to stop anyone from trying to replicate Damascus steel.

Back in the 1980s, two metallurgists at Stanford – Jeffrey Wadsworth and Oleg D. Sherby – accidentally came across a modern method. They produced something akin to Damascus steel while trying to make a "superplastic" metal of high-carbon steel. They estimated their sample at around 1-2% carbon, versus a more common < 1% for most modern steel. They discussed their process in the paper On the Bulat—Damascus steels revisited.

Another theory from researcher Peter Paufler and others at Dresden University suggests that Wootz steel blades look something akin to carbon nanotubes under the electron-microscope. Could the impurities noted by Verhoeven et al. perhaps have contributed to carbon nanotube growth? Perhaps – but Verhoeven, it should be noted, disagrees that nanotubes are special in the Wootz samples, stating, "I think those structures would be found in normal steels."

It's all intriguing, but don't hold your breath – especially if ancient Damascus comes down to a lucky combination of process, impurities, and a special deposit near India.

Today's Damascus steel blades may not be the same ones weilded back in the time of Alexander the Great, but they still have legendary, unique patterns with sharp edges and a reliable overall build. It's no wonder you find so many Chef's knives, santokus, and other kitchen knives using the modern process.

They'll look good in your kitchen, and you probably don't have to worry about replacing them anytime soon. Just watch your fingers – they'll let you know how sharp they are.