What fruit inspires cultivar names like Baby Boo and Warty Goblin, makes a great-tasting beer, and was an everyday dinosaur snack thousands of years ago?

(If your guess was the pumpkin, you've probably read the title of this article.)

Jokes aside, there's so much more to pumpkins than what meets the eye. From its domestication 10,000 years ago to its journey across the Atlantic in 1492 to its status today, the pumpkin's history is fascinating – and well worth a look.

There is no wild counterpart to the field pumpkin that exists today. Today's pumpkins are byproducts of domestication and evolutionary pressure form humans – some are grown for consumption, while some are for show or even everyday use.

Pumpkins belong to the Cucurbitaceae family and are specifically part of the C. pepo species, full of summer and winter squashes. Gourds, spaghetti marrow, zucchini, cocozelle, squash, and Ozark melons are all just variations in this group. Some cultivars of related species – C. argyrosperma and C. moschata, for example – are known as 'pumpkins' as well. And those giant pumpkins in all the record books? They're almost always from the species C. maxima.

Pumpkins – no matter in which species – are extremely diverse, and come in captivating colors, sizes, and shapes. Some are pale and white, like the Lumina and Casper varieties. Others are large and showy with green and orange splashes, like the Speckled Hound or the Hooligan.

The Porcelain Doll F1, a relative newcomer, is a surprising pink pumpkin while the Rouge Vif comes in vibrant red hues. In terms of size and texture, pumpkins range from small to large and can have smooth, flat, or bumpy skin. Some are enormous, thousand-pound lumpy giants (like the C. maximas mentioned!) while others can fit in my toddler's palm.

The larger ones often don't taste very sweet, while others, like the Sugar Treat pumpkin, are perfect for desserts and pumpkin pies.

Most pumpkins need plenty of water, sun, and nutrients in the soil to thrive and grow. But they're certainly hardy and adaptable – pumpkins grow on every continent except Antarctica.

They are relatively easy to grow and require a soil pH level between 6.0 to 6.5 for the best yield.

Pumpkins cannot grow in frosty conditions and need warmth. It takes field pumpkins between 75 - 100 days before they are ready for harvest, so it's best to plant them in the early summer.

The field pumpkin is a highly nutrient-dense food that is low in calories but rich in vitamins and minerals. Today's pumpkins' macronutrients and health benefits are pretty compelling, and it's even suitable for your pets.

Field pumpkins are nutritious, high in fiber, potassium, and riboflavin, and low in fat. They contain vitamins K, B6, C, and E, and are plentiful in beta-carotene.

On the flip side, all squashes produce biochemical compounds known as cucurbitacins. These biochemicals lend squashes a bitter flavor, and specific cultivars have more cucurbitacins than others. Overdosing on them can cause adverse GI effects and even hair loss(!), so it's best to pick a cultivar raised for eating just in case.

Pumpkins are versatile in the kitchen and taste great in both sweet and savory dishes. Even its seeds are edible, and one medium-size pumpkin produces roughly a cup that you can salt, roast, and enjoy.

Pies, soups, dessert, puddings, curries, breads, and cakes are all foods that incorporate pumpkin. The fruit also makes for a tasty beer, a practice adopted by the early pilgrims after settling in the Americas.

The main reason we still have pumpkins today is due to Native American farmers. The farmers fed pumpkins to their livestock, used them as tools, or incorporated them into their diet. Squash, corn, and beans – affectionately known as the Three Sisters – were the core components of Native American agriculture and spread to the rest of the world by the European settlers.

The Three Sisters grew well together and provided the nutrition the tribes needed to supplement during the cold winter months. Around 10,000 years ago, wild pumpkins and squash went extinct, and the pumpkin varieties that we have today are the direct result of their domestication and presentation by the natives.

Cucurbitaceae are native to Central America and are indigenous to Mexico, Peru, Ecuador, and Colombia. Our modern-day pumpkins are the result of thousands of years of careful selection. Breeding out undesirable traits and keeping the beneficial ones made pumpkins less bitter and more desirable to humans.

Some squash seeds found in a Mexican cave in Oaxaca are between 8,000 – 10,000 years old. The first gourds on the continent would have been small and hard to the touch. Although those cultivars were unsuitable for eating, Native tribes would have used them as tools to help them drink, eat, and fish. Moreover, the plant is a giver – dried pumpkin strips were (and are still, for some cultivars) strong enough to weave into mats.

As the tribes transitioned from hunter-gatherers to farmers, their agricultural methods began improving. The pumpkins and squash started resembling the shapes and sizes of the field pumpkins we have today, with better taste and form.

Native Massachusetts Tribes called squash askutasquash, meaning "to be eaten uncooked," and these were today's field pumpkins' ancestors. Cucurbitaceae derives from the Latin "gourd," while pepon means "large melon" in Greek.

The French, borrowing from pepon, pronounced pumpkin as pompon. When the French explorer Jacques Cartier passed through St. Lawrence, the "gros melons" (or big melons) he wrote about were, in fact, pumpkins.

The English used the term pumpion to refer to pumpkins, and they even made an appearance in William Shakespeare's 1602 play Merry Wives of Windsor. Today's pronunciation of pumpkin results from the American colonists' further alteration of that infamous English phrasing.

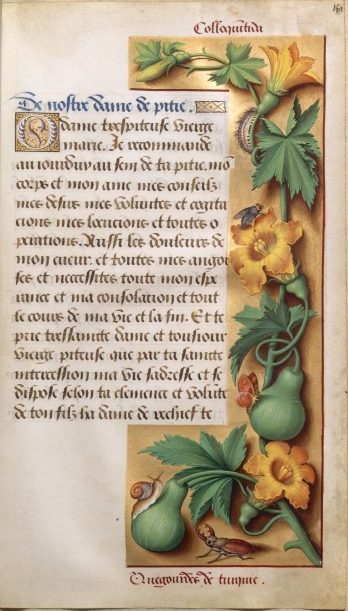

Pumpkins made their debut in Europe in 1492. The earliest reference to their existence in Europe comes from the prayer book of Anne de Bretagne, Duchess of Brittany, in the early 1500s. The prayer book's illustrations show a living Cucurbita pepo vine with fruits and flowers.

Christopher Columbus was the first European to bring pumpkin seeds from the heart of the Americas to Europe. He was also part of the first European group to set their eyes on a pumpkin patch, an event in Cuba on December 3, 1492.

Europe had melons and Curbita gourds at the time, but they were vastly different from the pumpkins that came from Central America. It took some time for pumpkins to gain popularity in Europe, but attitudes shifted by the 16th century. Countries like France and Spain began growing pumpkins on a mass scale, and their use increased. France, especially, is owed a lot of credit – you can find early pumpkin recipes dating to those years.

Initially, the Puritans weren't too impressed with Native American pompions, but the sentiment didn't last long. As hunger and harsh reality set in during the first Thanksgiving, winter squash and pumpkins were a reliable food source that fed livestock – and lasted through the winter. This pumpkin's versatility made it easy to include in food, and the early settlers came up with creative ways to consume it.

Although pumpkin pie makes an appearance in almost every modern Thanksgiving meal, the first meal between the pilgrims and the natives almost certainly didn't include a pie course. There was neither butter nor flour to make a crust, so they used other methods to incorporate pumpkin into their dishes. In one possible recipe, settlers would have hollowed a pumpkin and filled it with milk, honey, and spices to make a custard while roasting the whole package over hot ashes.

Dutch landowner Adriaen van der Donck made extensive observations of how early Americans enjoyed their pumpkins. Pumpkin made its way into stews, brews, and later on into pies in the Puritan diet. The later cookbook, American Cookery, includes a recipe for pumpkin pie with apple and spice filling. Authored by Amelia Simmons, the book also has a recipe for pumpkin pudding.

One of the earliest and more exciting pompion recipes comes from the 17th-century book written by New England traveler John Josselyn. The dish calls for boiling diced pumpkin for a day and stewing the remains. Then: add butter, vinegar, and ginger to the mush, and don't forget your protein of choice such as fish or "flesh." Josselyn warns that the recipe causes frequent trips to the bathroom and a "windy" stomach.

Aside from their culinary uses, pumpkins also have a surprising connection to the abolition movement. The early settlers did not have an easy time adjusting to their new homes. They had to face challenges that included strife and starvation, and the majority of the early settlers faced hardship.

At the forefront of these hardships were women who worked in the fields. These women also had the additional duty of bearing and rearing children. Perhaps because of this, women were also the pioneers of the abolition movement, which worked to end slavery in America. The symbol of those hardships and triumph was the pumpkin, which had a place at every table.

Famous abolitionist Sarah Josepha Hale mentioned pumpkin pie in her book Northwood, published in 1827. Poet Lydia Maria Child added pumpkin pie to a verse in her 1842 Thanksgiving poem, usually known as Over the river, and through the wood. In that way, pumpkin became part of the northern states' push to make Thanksgiving a national holiday – eventually established by Abraham Lincoln in 1863.

The advent of industrialization and the growth of the economy led to the mass production of goods. Pumpkins became part of the trend, and the marketing of the time is what you'd expect: calls to avoid the dangers of preparing pumpkins while embracing the convenience of a readily-canned option. No longer did homemakers have to plant, store, and prepare their own!

The ability to can and freeze foods increased the availability of pumpkin products throughout the country. Industrialization also meant an improvement in farming processes, which increased yield – a trend that continued until today. Every year, US farmers collectively grow over 1.5 billion pounds of pumpkins.

Today, pumpkin flavors abound in American products and have migrated to all sorts of goods: everything from candles to – yes! – pumpkin spice lattes. Pumpkin and pumpkin spice have grown to symbolize the fall season.

I'd be remiss if I didn't mention one of the more famous pumpkin decorative uses: the famous Jack O'Lantern!

As you've seen, pumpkins are part of the American fabric and the immigrant story. But on the Jack O'Lantern side, they also figure into Celtic tradition among Scottish and Irish immigrants

Samhain, a Celtic holiday, is considered the night when the veil between the spirit world and the material world lifts. People would place carved lanterns – often scary figures carved out of turnips and other root veggies – on their porches to welcome spirits of their loved ones on this night. The lights would also scare the negative spirits away.

It turns out pumpkins are better for this purpose than turnips. Early immigrants quickly embraced the orange gourd, and the tradition of carving Jack O'Lanterns continues to this day as the most famous – and spooky – symbol of Halloween.

The Jack O'Lantern is renowned because of Ireland's old tale about Stingy Jack and the mistake he made that cost him his soul. You see, Jack was incredibly clever – so clever he was able to trick Satan a few times.

As the legend goes, Stingy Jack made a pact with the devil and (as most retellings go) eventually tricked him into agreeing he could never go to hell. As Jack wasn't exactly a good person, he also wouldn't be able to get into heaven upon his death.

As a result, Jack was neither able to go to heaven nor hell – doomed to roam the earth. Once he died, the devil turned Jack away but provided him a candle and asked him to find his own hell. He put the light inside a turnip. The turnip evolved into the pumpkin from those early immigrants, and the light one sees in the Jack O'Lantern (and lights over swamps, known as Will-o'-the-Wisps) is said to be Jack's soul.

Many Halloween traditions and stories revolve around our favorite winter squash. But two have really ingratiated themselves in Halloween's culture: the Headless Horseman and The Great Pumpkin.

Washington Irving's 1820 story The Legend of Sleepy Hollow is the most famous American pumpkin tale. In it, schoolmaster Ichabod Crane battles Brom Bones for the affections of Katrina Van Tassel. Returning home one night, he encounters a headless horseman who pursues him over a bridge and hurls his severed head at Crane, making a direct impact.

Crane's body was never found – the only evidence of the chase was Ichabod's hat, and a shattered pumpkin... perhaps the head of the horseman?

Christmas has eggnog and candy canes and Santa Claus. Halloween has candy corn and chocolate and... well, who?

Charles Shultz answered that question in his beloved comic strip Peanuts. One of the characters, Linus, believes that The Great Pumpkin visits a deserving pumpkin patch every Halloween.

Linus eschews trick-or-treating, choosing to spend time in the pumpkin patch waiting for the Great Pumpkin's arrival. He has various success convincing others to stay up with him, but, alas, never catches a Great Pumpkin glimpse.

Pumpkins can grow to enormous proportions. The current record holder for the biggest pumpkin ever grown is Mathias Willemijns from Belgium. His pumpkin weighed a whopping 2,624.6 pounds and made the Guinness Book of World Records.

Several factors lead to the formation of a giant pumpkin. In addition to the pumpkin species, other elements like the seeds, soil, and fungi surrounding it make a difference. The Cucurbita maxima is the species known to yield the biggest pumpkins, and from there, time and cultivation produce the massive results we see today.

Throughout this article, I refer to the pumpkin as a fruit, which's not a mistake. Although many people see the pumpkin as a vegetable, it is actually a botanical fruit! Like the tomato, we are used to calling this plant a vegetable, but it's a berry, not a vegetable.

However, just like tomatoes, cucumbers, and green beans, it's a fruit and a culinary vegetable.

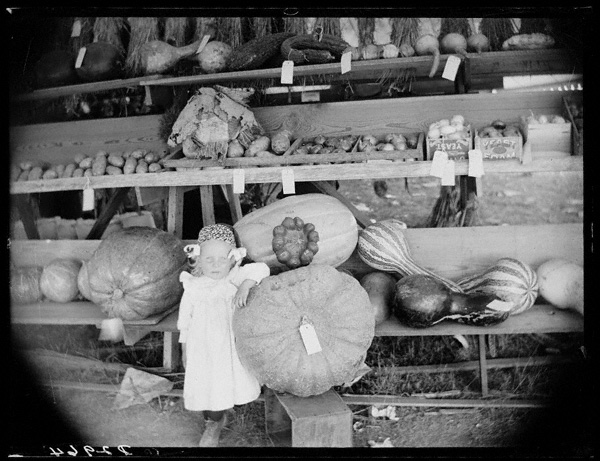

There are many activities and events held in honor of the pumpkin both in the United States and worldwide. Pumpkin carving is an event that American families enjoy every fall. Going to the pumpkin patch (and picking the perfect gourd to take home – as seen in the photo below!) is a yearly tradition that millions of people look forward to with their loved ones.

One example of a more esoteric hobby is Pumpkin Chunkin, a competition where people make devices that hurl pumpkins in the air without electricity.

The most famous of all the gourds is undoubtedly a fascinating subject. It's been everywhere, from Central America to Europe to your Thanksgiving table. It inspires controversy in candle scents and lends a name to pumpkin spice lattes. And it scares children come Halloween.

Truly, the pumpkin is a fascinating vegetable – err, fruit. So as you carve up a mean-looking Jack O'Lantern this Halloween, think about the history of the pumpkin and how it got where it is today.