If you've got kids, try saying "pizza" at anything louder than a whisper. If they're anything like mine, they'll come running.

What is it about this topping-adorned flatbread? Have you ever wondered just how this meal came to be?

The history of pizza will surprise you. It has humble beginnings as a "lower class" food, but nowadays it's big business for everyone – so let's take a huge bite together and explore pizza's history and origins.

When we think about pizza, most of us don't automatically think about flatbreads like focaccia. But you've got to draw the line somewhere, and flatbread's evolution to modern pizza means we're also overlapping with the general history of bread.

Humans have enjoyed flatbread since, well, at least 22,000 years ago. But those early flatbreads require too much squinting to trace a direct line to pizza. The path to pizza really starts with focaccia – a roughly 3,000-year-old flatbread topped with some very familiar ingredients.

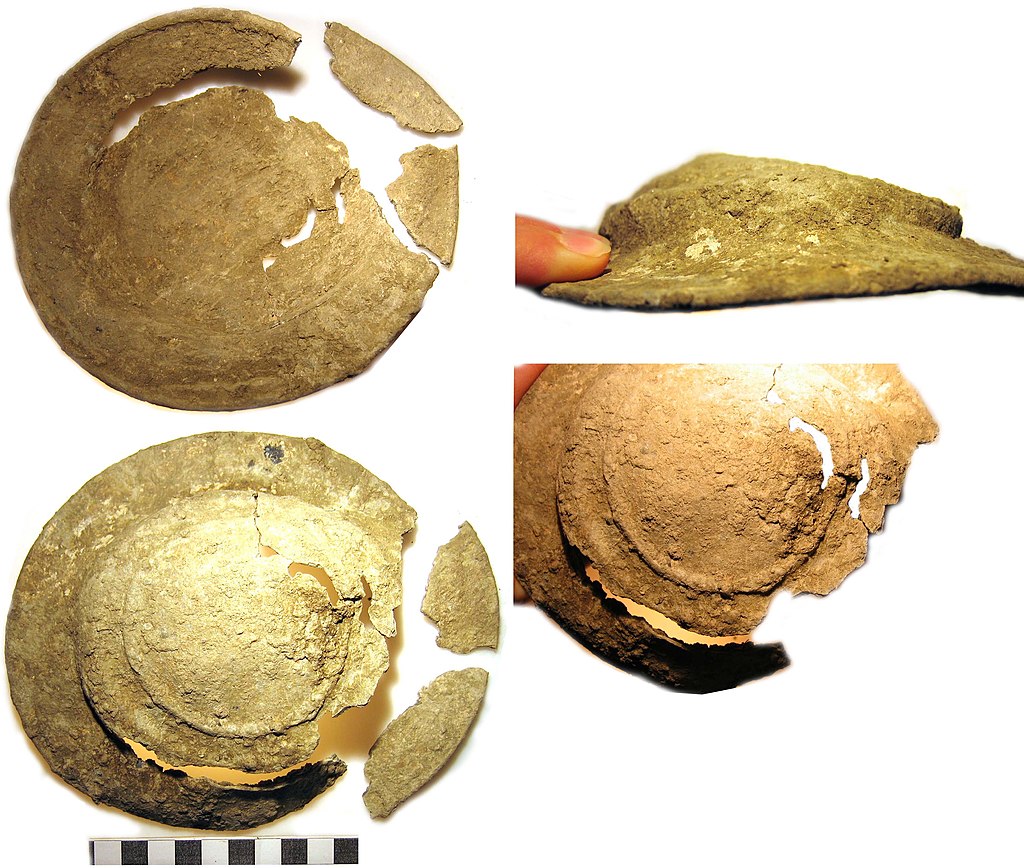

The Etruscan civilization, which settled around 900-800 BC on the Western Coast of Italy, likely invented focaccia bread. They'd top their flatbread with herbs, spices, and olive oil and heat the flatbread on a hot tile or an earthenware disk over a fire, often under hot ashes. The Romans called this bread "panus focus," or focaccia in Italian.

They topped this bread with oil, herbs, nuts, and seeds – a familiar practice echoed by today's pizza toppings. It's closely related to today's pizza bianca, more often cooked directly on the oven floor than a pan (although pizza bianca should tend to have fewer toppings!).

And it wasn't just the Etruscans and the Romans dressing up their bread. Various cultures – including the Israelites, Egyptians, Greeks, and Phoenicians – made and enjoyed flatbread thousands of years ago. All these cultures made their flatbread from water and flour, flavored with various herbs, spices, and oils. Like the Etruscan flatbread, many of these breads were also cooked by placing them on hot, flat stones.

Famously (and yes, the Greeks have a claim they invented the pizza), the Greeks referred to their flatbread as "plankuntos," which they'd top with fruits, stews, or meats. Plankuntos was also used as an edible plate by the Greeks, and there are still cultures in the Middle East that use flatbreads as edible crockery today. Maneesh is an example of this—it's a thin bread sprinkled with herbs that is still used today as a plate to eat tabbouleh, hummus, or even mutabal.

Marcus Porcius Cato—also known as Cato the Elder—mentioned bread in his famous manuscript De Agricultura, which is the oldest known piece of Roman literature, from 160 BC. He included a recipe for bread in the book, much like our recipes today—using flour and water, kneading the dough and baking it under an earthenware lid.

Cato also wrote about "a flat round of dough dressed with olive oil, herbs, and honey baked on stones." So, somewhere in the years between the Etruscans and Cato the Elder, the Romans baked circular bread. A hundred and fifty years later, Virgil's epic poem The Aeneid talks about soldiers eating the very 'plate' or 'table' they serve the rest of their food on – a predecessor of the variety of pizza toppings, perhaps?

Even though the flatbreads of different cultures vary in spices, herbs, and toppings, the most common thread between them is that there was no tomato in the original recipes. And, truly, the history of pizza is the marriage of the circular Meditteranean flatbreads we've been discussing with the tomato – a fruit originating in the Americas.

Which leads to the next obvious question—how did flatbread and olive oil turn into pizza with tomato? I'm glad you asked.

Despite popular thinking, tomatoes aren't native to Italy or Europe—tomatoes originated in Central and South America. There's also evidence that the Inca and Aztec tribes were eating tomatoes and cooking with them as early as 700 AD.

Two legends explain how tomatoes arrived in Italy. One states that two Jesuit priests brought the fruit with them to Italy; the other that either Christopher Columbus or Hernán Cortés introduced tomatoes to Europe (more likely).

Although the trans-Atlantic travel is unclear, the first recorded mention of tomatoes in Europe was in Mattioli's Herbal in 1544*. But tomatoes weren't well-received, and people thought they were poisonous—and avoided using them for almost 200 years. Seriously, tomatoes were cursed – check out my tomato history article; it's a crazy story.

*Officially: Di Pedacio Dioscoride Anazarbeo Libri cinque Della historia, et materia medicinale tradotti in lingua volgare italiana da M. Pietro Andrea Matthiolo Sanese Medico, con amplissimi discorsi, et comenti, et dottissime annotationi, et censure del medesimo interprete

To understand the "poisonous" history of the tomato, know that many in the upper class used pewter plates with high lead content. Acids in tomato could react with the leaded pewter, drawing out the lead and contaminating the food. This resulted in lead poisoning deaths, and the tomato was nicknamed the "poison apple."

The lower class had a different reaction – their plates were made from wood or other materials, which had no adverse reactions with tomatoes. Thus, they started cooking with tomatoes more often to add flavor – due to that strange quirk of history, tomato dishes could only have come from the "lower" classes.

And, let's face it, tomatoes taste good. From there, the popularity of tomatoes grew as the demand for "peasant food" increased.

Who invented the pizza? We'll never know, but the first pizza as we understand pizza today almost certainly came from Naples. The lazzaroni—people of lower social standings (and often dockworkers)—needed a quickly prepared and eaten food. Pizza certainly fits the bill.

Since the upper classes avoided the tomato, they pretty much ignored the development (you won't find pizza in any early cookbooks).

But – you can't keep a good recipe down. From the mid-1700s, street vendors hawked pizza to workers, and eventually, taverns and bakeries got in on the action and sold pizza from a fixed location.

Food historian Antonio Mattozzi lists at least 54 fixed pizzerias by 1807, doubling in the next 50 years. One early pizzeria you can still visit today is the Antica Pizzeria Port'Alba, evolving from a street vendor in 1738 to the fixed store in 1830.

And the rest, from those humble beginnings, is history. You'll even recognize two of the popular pizzas from the 1700s-1800s:

And there-s more – you can visit many of those early Naples pizzerias today.

Then – there's the Margherita pizza, pizza that's fit for a queen! (Or so the story goes – more about that in a second).

In 1889, Queen Margherita of Savoy was touring Naples. She requested that Raffaele Esposito—Naples' best pizza maker—cook for them. Raffaele created three different pizzas, one of which resembled the Italian flag, with traditional green, white and red toppings:

Purportedly, the Queen so loved the pizza, and in her honor, Raffaele named it the "Margherita." Charming, but perhaps apocryphal – the Queen's "thank you" letter certainly has some issues that suggest a forgery. Regardless of the Margherita's origins, the name certainly stuck – thus our discussion today. (The pizza probably dates to 70-90 years earlier.)

Whether 200 years old or 130, this classic pizza has stood the test of time. And so has the pizzeria: the Pizzeria di Pietro e Basta Cosi, which Raffaele owned, is still making pizza today, and it proudly displays the Queen's alleged letter of thanks.

Also, mozzarella cheese came about in the 18th century, giving rise to the classic pizza base we know today—with tomato sauce and cheese.

Pizza, and the related history of pizza, is a vital part of Naples' history—so much so, that the European Union has strict standards for what they allow to get the label "Neapolitan-style pizza."

For the European Union to classify a pizza as a genuine Neapolitan pizza, the pie must have a raised crust, and the base can't be more than 1/8th of an inch thick. Also, the maker can't flatten the dough using a rolling pin—it must be hand-made and cooked on a stone slab in a wood-fired oven.

There's also an Italian trade group—the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana—which dedicates itself to protecting Naples' history of pizza. For instance, it says that for a pizza to be a true Margherita, it can only use the following toppings:

Safe to say, the Associazione Verace Pizza Napoletana takes pride in pizza. With the worldwide spread (and awareness) of traditional foods, it's a worthy task. Directives like the EU's and the Associazione's efforts hold pizzaiolis—master pizza makers—to a very high standard.

With efforts like these in place, even though the original pizzas have already been eaten – you can still eat a faithful, traditional pie today.

As the Americas introduced the tomato to Italy, eventually Italy presented America with the pizza. And, it's safe to say, America ran with it.

In the late 1800s, the Italian economy took an unfortunate turn, leading to more than four million Italians immigrating to America. At this time, Americans considered pizza an ethnic food, and Italian street vendors in the cities they settled in—especially New York—sold it just like they had in Naples. But the street vendor pizza scene didn't last long.

In 1905, a gentleman by the name of Gennaro Lombardi (or, possibly, Filippo Milone) opened one of the first US pizzerias in New York – aptly, Lombardi's. This was the catalyst, and soon, pizzerias were opening in other parts of New York, Connecticut, and New Jersey.

In 1910, Joe's Tomato Pies opened. It was the first to serve what's known as the "Trenton tomato pie"—otherwise known as New Jersey tomato pie—which was a thin, circular-crust, Italian tomato pie. The cheese and other toppings came before the sauce, which used crushed, whole, plum tomatoes.

But it wasn't until World War II was over that pizza really began to gain popularity in the States, largely due to the American soldiers who'd returned from the war—they'd developed a taste for it while serving on the Italian Front during the war.

Pizza got another boost when the press shared photos of Italian celebrities, such as Joe DiMaggio and Frank Sinatra, eating it in 1950. I Love Lucy's Lucille Ball took a brief pizza-making job in 1956. And, with the celebrity endorsements, Americans started to take note of pizza.

Shakey's Pizza was the first franchise pizzeria to open in 1954. Within a decade, it had stores in 342 locations. Today, it's an international brand that's listed on the Philippines Stock Exchange.

Over the next few years, pizza continued to grow in popularity. In 1958, two brothers—Frank and Dan Carney—took a loan of $600 from their parents and opened a 25-seat pizza parlor. The brothers called their business, "Pizza Hut," which was partly because the sign they'd bought didn't have space for any more letters.

By the early 1960s, Pizza Hut was growing from strength to strength, and by 1966, they had 145 branches throughout America. In 1968, they'd opened stores in Canada and were already at 1,000 stores by the early 1970s. Today, Pizza Hut is an international brand, with stores in nearly 100 countries and with over 11,000 Pizza Huts worldwide.

While Italian immigrants to America, war, and celebrities drove pizza's popularity, one thing's for sure: there are many varieties of pizza. From those classic flatbread beginnings to the strange history of deep-dish pizza, creators have exercised their pizza creativity.

As pizza grew in popularity and franchises were on the rise, another pizza was making headlines—the Chicago-style deep-dish pizza. Its creators, Ike Sewel and Ric Riccardo, opened their first store in 1943, Pizzeria Uno and Uno Chicago Grill.

What makes the Chicago style different? Firstly, it's deep-dish; secondly, the order in which it's made is unique.

Your non-deep dish pizza gets made in the following order:

The Chicago deep-dish pizza gets made in the following order:

Far be it for me to declare a winner. But please, share this post and comment to let me know if you prefer deep dish pizza or the more standard American style!

Never heard of the smoked salmon pizza? Oh, it's a thing.

The smoked salmon pizza is the signature dish at Wolfgang Puck's restaurant, Spago.

The inspiration behind this delectable pizza was Joan Collins—she ordered a smoked salmon with brioche, only the restaurant was out of bread. Wolfgang rose to the challenge and, instead of brioche, layered the smoked salmon on a pizza crust.

California style pizza also traces its origins back to Wolfgang Puck. Ed LaDou created the California pizza by enjoying experimenting with different pizza styles, culminating in serving Wolfgang Puck one of his creations.

His pizza impressed Wolfgang, and he went on to hire LaDou for his Hollywood restaurant, Spago. LaDou was one of the most influential people in the development of the California-style pizza, and he eventually created a range of vegetarian pizzas.

So what makes the California-style pizza different? It's a combination of other styles—a single-serving pizza with a thin-crust, which mirrors traditional Italian crusts or the New York-style pizza, mixed with "California style" toppings. But the real difference is in the toppings—organic toppings such as avocado, artichoke hearts, goat cheese, and peppers abound, plus options for vegans and vegetarians.

The pizza we know today comes in many forms—powdered, frozen, or fresh. While each of the inventions and trends that brought us to today deserves their own post, let's highlight two that brought pizza back into the home.

In 1948, Frank Fiorello created Appian Way pizza mix, or "Roman Pizza Mix," which was also the first known commercial pizza-pie mix.

Joseph Bucci filed the first patent for making frozen pizza in 1950. The next few years saw fits and starts as Americans got used to the idea of frozen pizzas – and by 1954, the Washington Post and New York Times were writing about the trend.

Frozen pizzas really started to take off in 1957. The Celentano brothers owned an Italian store that sold Italian specialty produce, including meats, pasta, and cheeses.

The brothers created a frozen pizza that came in squares, and they were the first brand to go national with this new style of pizza. And the rest, as they say, is pizza history – pizza is now one of the most popular frozen foods.

As you may know, Hawaiian pizza was invented by a Canadian: in 1962, Sam Panopoulos was the first to add pineapple to pizza. Sam became inspired by his experience making Chinese dishes, with their blend of savory and sweet flavors. Based on Chinese recipes, he started experimenting with a variety of ingredients (which weren't well-received at first.)

It was only when Sam added pineapple to the cheese and tomato sauce along with ham or bacon that his creation gained popularity. This marked the birth of the Hawaiian pizza, now a classic on pizza menus all over the world. It's also an extremely popular fight – do you think pineapple is a good pizza topping?

Sam was creative, but he wasn't as creative when he named the pizza—he named it after the brand of canned pineapple he used.

Americans love pizza so much that they've given it its own day—they celebrate National Pizza Day annually on February 9th.

Pizza was originally sold by the pie. In 1933, Patsy Lancieri started to sell pizza by the slice—other pizzerias quickly adopted this. Let's not leave him and his wife Carmella out of the history of pizza—the single slice is an important part of pizza culture today.

The world's most expensive pizza—the Louis XIII—costs around $10,000, and you can buy it in Salerno, Italy.

It is, however, no ordinary pizza. A chef will come to your home kitchen and create the pizza before your eyes. The dough arrives with the chef, aged to perfection. Some of the ingredients you can expect on this pizza are:

And, no, I don't think you can buy it by the slice. But – it's only 20cm in diameter, so if you've got a big appetite, you can probably eat it solo!

We're 3,000 words in, and I'm only covering the surface (the toppings?) of the history of pizza. Suffice to say: it may have been invented in Italy, but it is a global tradition now. Marrying a long tradition of European flatbreads with America's tomato contribution, pizza is popular worldwide – and in my home, to boot.

Next time you order pizza, think back on its rich history and smile. You're in good company – I hope you enjoy your slice.