Aluminum foil – sometimes incorrectly called tin foil – is a thin, prepared sheet metal made of aluminum, often used in cooking (and food storage!).

Although it may seem a little dull at first glance (especially on its dull side), aluminum foil has quite a fascinating story behind it. Many incredible things occurred before it became a staple in the modern kitchen.

In this post, I'll discuss the various events that led to the aluminum foil revolution, and highlight the continued importance of this seemingly mundane material in our lives.

Aluminum foil is a thin sheet of metal foil or metal leaf composed of an aluminum alloy containing roughly 92–99 percent aluminum. It usually has a thickness between 0.0002 to 0.006 inches, but its width and strength vary greatly based on the intended application.

Just some of those applications include:

The popularity of aluminum foil stems from the fact that it's a highly versatile product that can be used in limitless ways. It's a durable, non-toxic, greaseproof material capable of resisting chemical attacks. It also offers decent magnetic shielding and is an excellent electrical conductor.

The best part? Making the foil itself is a relatively inexpensive process.

The packaging industry captures the vast majority of the aluminum foil market. As the foil is nearly impermeable to gases and water vapor, it's used in various products – from foodstuffs to gifts!

Foil can extend the shelf life of products, it takes extremely little storage space, and it produces lower waste than its counterparts. With all these positives, it's evident why aluminum foil is so popular.

Aluminum foil is made by converting billet aluminum into rolling sheet ingots. This process is replicated in sheet and foil rolling mills to obtain the desired thickness.

Concerning the debate between the shiny and dull sides: there's no "right side" of a foil sheet. The texture differences only arise due to the manufacturing process itself, and either side of aluminum foil is safe to use.

The fact that aluminum foil is entirely recyclable makes it a great asset in the quest for greener living. As long as your aluminum foil isn't dirty, you can reuse it in the kitchen.

And its usability in the kitchen is legendary. It's used in packaged products such as cream cheese and candy, you can use it to store leftovers, and you can even use it as a cooking surface.

And why stop at a surface? The Boy Scouts introduced the world to the magic of hobo packs, which involve placing cut-up pieces of various ingredients in foil and roasting them over a fire.

While most people are more than happy to refer to aluminum foil as tin foil, in reality, they are two vastly different materials. However, the story of aluminum foil is certainly incomplete without briefly discussing the history of tin foil.

Tin foil's history goes back a bit longer than aluminum foil's. Tin is a soft metal, just like aluminum. The use of tin and tin foil in various capacities dates to the late 18th century.

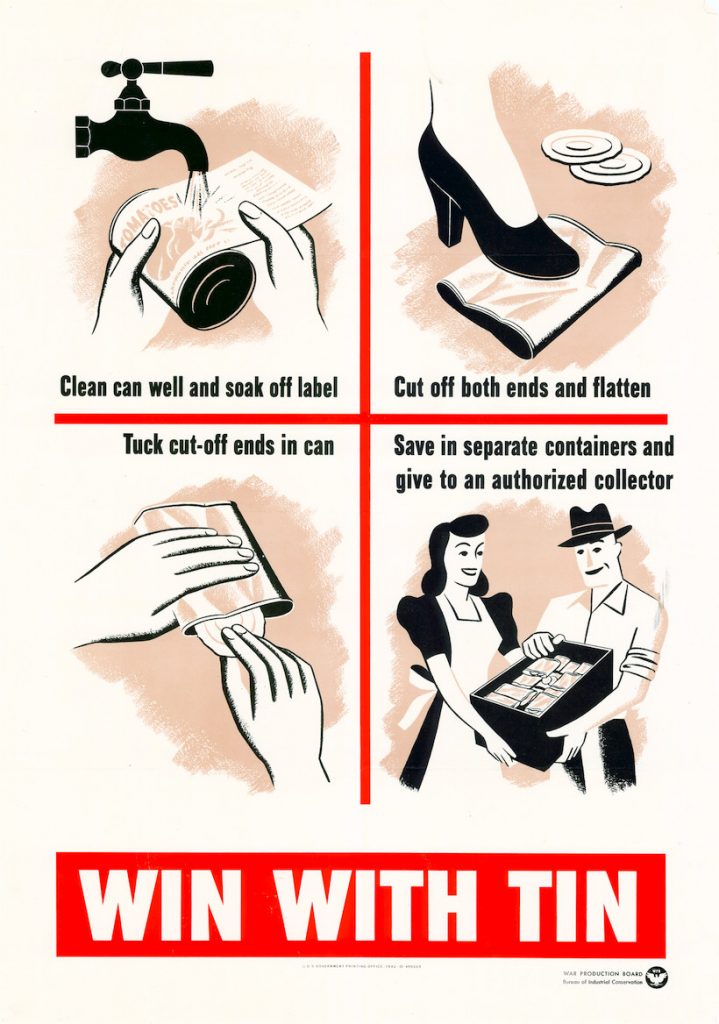

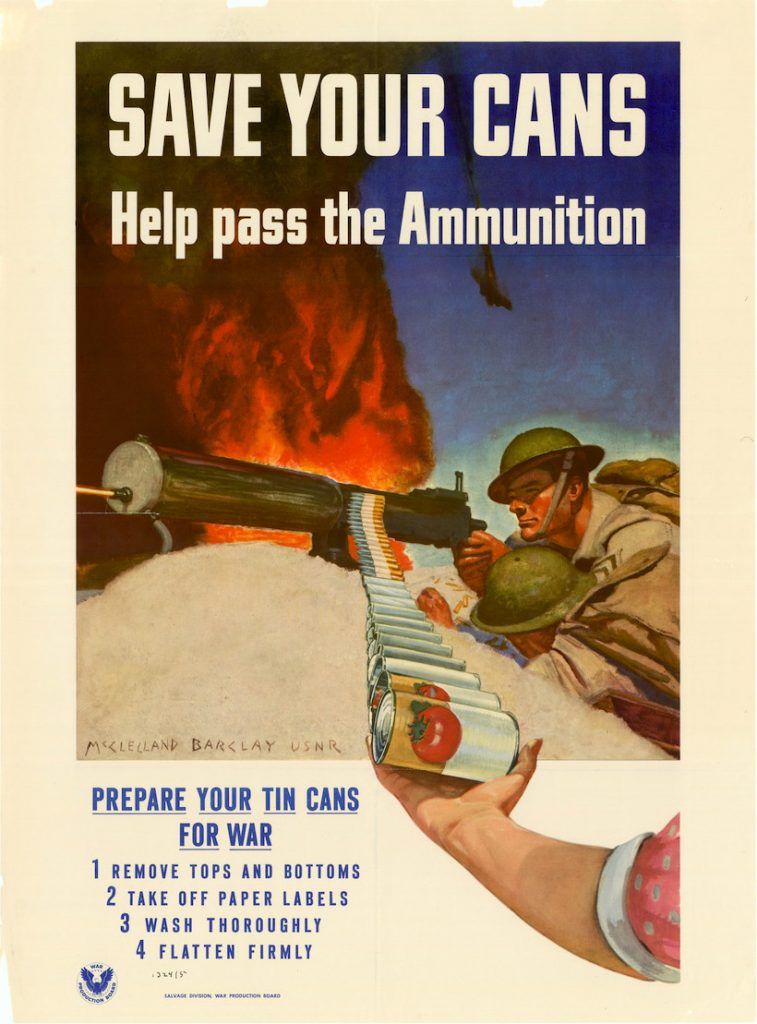

Tin foil didn't fall out of common usage in the United States until World War II. Tin is rarer than aluminum, and nearly all tin was imported into the United States at the time (or recycled). The US's War Production Board even mandated larger towns had a tin collection process in place at the time.

Aluminum is abundant, doesn't leave as much of a taste signature in food, and is roughly otherwise equivalent.

A Win-win!

But still – let's look at a few notable and interesting uses of tin foil.

Thomas Edison used tin foil wrapped around a cylinder to create the first recording device for a phonograph.

This worked far better than his previous material: paraffined paper. The tin foil was thin enough and sensitive enough to make the necessary indents during the recording process.

Another surprising application of tin foil was its use in dentistry. It was used as filling material as early as 1783, and there's historical evidence from a book by H. Ambler from 1897.

The benefit? The flexible nature of tin foil allowed it to be reshaped to take the space between the cavity and act as the ideal filling material during this era.

Tin entered food packaging during the 19th century replacing the mason jar, and it was extensively used until the mid-20th century when aluminum foil took over. While tin foil was popular, the most common relic of the time is the still-in-the-lexicon tin can.

Ultimately, it was a good swap. Food wrapped in tin foil or packed in tin cans tended to take on a "tinny" taste. For tin cans, especially, manufacturers added more and more complicated sealing and coating procedures. Aluminum avoids those downsides.

The story of aluminum began as early as 1808 when British chemist and physicist Sir Humphry Davy experimented with a process known as electrolysis. He used it to extract a host of new elements such as potassium, boron, calcium, sodium, and magnesium.

After achieving success on these various fronts, he realized that this same process could extract aluminum from aluminum oxide.

A few years later, in 1821, a red rock was discovered in the south of France dubbed Bauxite. Although Pierre Berthier discovered the rock, it was named after the region in France where it was found — Les Baux. It has had an integral role in aluminum production over the years and still serves as an abundant resource.

The first actual aluminum extraction occurred in 1825. Danish physicist Hans Christian Oersted used to isolate aluminum for the first time. Well, so the story goes – his process probably led to a too impure extraction.

Many scientific minds would dedicate themselves to creating superior versions of the aluminum extraction process from this point onwards. Friedrich Wohler, a German chemist, managed to take the process to its next stage of evolution. By 1827 he was extracting pure aluminum powder, then by 1845, he successfully created small balls of aluminum in a solidified melted form.

In the mid-1800s, Henri Étienne Sainte-Claire Deville started working on his version of the electrolysis process to extract pure aluminum. This would significantly advance the field, and other scientists would launch their work off his process for years to come. His was also commercially successful for the first time – from the process's perfection in 1856 until 1890, his aluminum production scaled up to around 45 tonnes a year.

When aluminum first hit the markets in 1856, it made quite an impression on the general public. It resembled silver in its appearance, was expensive and lightweight, and could be molded to make jewelry and art.

Shortly after, in 1858, the first book (we believe) about the metal, titled "aluminum," was compiled by the Tissier brothers.

It wasn't until 1886 that the industrial-scale aluminum extraction process was perfected by two scientists named Paul Louis-Toussaint Héroult and Charles Martin Hall. Their process led to 99.5% pure aluminum.

The technique is still referred to as the Hall-Héroult process.

With the help of the new and improved Hall–Héroult process, Charles Hall and a few other individuals established a large aluminum smelter near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on September 18th, 1888.

The demand for the metal was booming during this period. The factory responded to the need – it scaled from 22.5 kilograms per day in its first month to 240 kilograms a day by the following year.

The factory was initially called the Pittsburgh Reduction Company, but it would eventually be renamed the Aluminum Company of America in 1907. Alcoa is still in business and trades on the New York Stock Exchange.

Surprisingly though, one of the most significant breakthroughs in the manufacturing of aluminum was still yet to come. In 1889, Carl Joseph Bayer, a chemist from Austria, managed to extract alumina from an alkaline solution known as aluminum oxide.

This process is known as the Bayer process, and it remains the technique used in the production of nearly 90 percent of all aluminum around the world.

The effect of these developments (and the general scaling of production) could be seen in the falling price of aluminum over the ensuing years. When aluminum particles were first extracted in 1825, aluminum sold for a shocking $525 per pound. Those prices continued to drop dramatically with each passing decade until a pound of aluminum was $14/lb. by 1942.

So in around 120-140 years, aluminum went from mystery metal to replacing tin as the dominant kitchen foil!

The 19th century was a period of transition from tin foil to aluminum foil for processes worldwide. Robert Victor Neher created a continuous rolling process in 1910 and managed to patent it in the same year. He then opened an aluminum rolling plant in Kreuzlingen, Switzerland.

Establishing the plant in Europe's heart offered various companies a chance to shift their current packaging methods. In 1911, the Tobler Company used aluminum foil to wrap its famous triangular chocolate bar, Toblerone. The following year, Maggi (now a part of Nestlé) used the material to package its soaps and stock cubes.

Another surprising use of aluminum was discovered by Richard S. Reynolds, the creator of Reynolds Wrap. He set up the U.S. Foil Company in 1919 to supply wrappers to candy and tobacco companies.

Until that point, like most others, the company relied on tin for their unique wraps. When the price of aluminum decreased in the 1920s, the company quickly shifted to using this lightweight and non-corrosive material. The fact that it could be rolled into thinner sheets than other existing alternatives was a big boon for Reynolds.

Once the shift to aluminum began, there was no slowing it down. By 1926, Reynolds began using aluminum foil to pack materials for the first time. This drastically improved their sales, which improved to $13 million by 1930.

In 1940, another interesting development occurred within Reynolds' brand when an employee (supposedly) used an extra roll of aluminum foil to save his thanksgiving dinner after being unable to find a pan for the turkey.

When the trick worked, the company expanded its aluminum push even further. The rest, as they say, is history – aluminum foil is dominant in cooking, and you can still buy aluminum bakeware at the supermarket today.

For all the advancements and fine properties, the Second World War was the primary reason factories' production shifted from tin to aluminum. During this period, Japan had control over 70 percent of the world's tin supply, which directly conflicted with America's needs.

Once this boom began at the local level, there was no turning back. Aluminum advancements continued to develop well into the second half of the 20th century, with new applications popping up everywhere. You'll certainly recognize a few – sealed TV dinners, cartons, and blister packs.

The rise of tin foil hats in connection to conspiracy theories added to the demise of the material. As tin is an okay electrical conductor and weakly magnetic, some believe it can stop "mind-reading" waves from escaping or "mind-controlling" waves from getting to your brain.

A 2005 MIT study tested tin's successor aluminum's ability to block radio waves and found that for some frequencies aluminum amplified the waves(!). Frequencies between 1.2 GHz and 1.4 GHz showed amplification in their tests – spectrum currently allocated primarily to research, GPS, and mobile frequencies.

It makes you think! (Also, I haven't seen a study on tin-based hats yet... what are they hiding?)

For the most part, yes, you can cook on aluminum foil sometimes without worry. Small amounts of aluminum should be okay from cooking, and some forms of aluminum are even GRAS – generally recognized as safe – by the FDA. However, you should avoid acidic foods on aluminum – for example anything with a tomato base, or with lemon on top.

Aluminum foil, aluminum cookware, aluminum cookware and the like can cause large amounts of aluminum to migrate to your food. Now – it's not as dangerous as lead, but long term aluminum exposure can cause issues.

Aluminum manufacturers have confirmed that there's no correct orientation for using aluminum foil. Both sides can be used for any purpose, and the difference in shine only arises due to the technique employed to manufacture aluminum.

The market size for aluminum foil globally is estimated to stand at 23.1 billion USD (as of 2018). It's expected to grow at a rate of 5.3 percent through 2025.

The recycling rate of aluminum is quite high when compared to other materials around the world. Nearly 85–95 percent of all aluminum used in the transport and building sectors ends up getting recycled. Concerning aluminum cans, approximately 30–100 percent of all cans are recycled based on the region.

For sure a versatile, everyday item, aluminum foil sure has a fascinating history. Aluminum's is a story of scientific advancement, continuous improvement, and human ingenuity.

The next time you're wrapping your leftovers or tenting your meat after grilling, consider just how impressive aluminum and aluminum foil's rise was over the last 200 years. Now let's eat!

Good work! A fun note - years back, a woman preparing baking dishes of food for a gathering, found that the food did not cook in its usual time. In fact, it was not cooking well at all after a half hour. She reasoned that it was because the foil on top had been turned shiny side out, reflecting the heat. When she rewrapped the dishes with the shiny side in, the food cooked more quickly.

At one time, a small ingot of pure aluminum was displayed with the crown jewels of England. Aluminum of that purity was almost unheard of at the time ingot was created, and had a high value, comparable to the value of other jewels in the collection.